By Gianni Simone.

Tadao Tsuge is the stuff of legend. Though, until quite recently, he was nearly unknown outside Japan, the veteran comic artist was one of the pioneers of alternative manga and a key contributor of avant-garde magazine Garo between the late 1960s and early 1970s. Differently from his older brother Yoshiharu, Tadao has extensively portrayed in unsentimental tones the gritty life of common people and their daily struggles in postwar Japan. Ironically enough, though brother Yoshiharu usually gets everybody’s attention, Tadao has had better luck in the foreign publishing world as three excellent books have been recently published in English. The manga stories mentioned in this interview can be found in Trash Market (Drawn & Quarterly), Slum Wolf (New York Review of Comics) and Tale of the Beast (Black Hook Press).

According to your essay at the end of Slum Wolf, when you were a child, apart from reading adventure and mystery novels, you were a big movie buff.

Yes, I liked any kind of film, but my favorites were Western movies. My family was poor and we didn’t have the money to go to the cinema, but I came up with several stratagems to get access without paying. I liked films that much. I kept doing this until I was about 13 or 14. Eventually they caught me. That was the end of my career as a movie-loving law-breaker.

How about manga?

I loved Osamu Tezuka, like everybody else. He truly was the god of manga to us; the Japanese Walt Disney. Many of the comic artists of my generation are dead now, but if you had asked them, they all would have given you the same answer. The kashihon rental manga were not always available, so we actually had to buy Tezuka’s comics. So my two older brothers and I did little jobs here and there then pooled our money to buy a comic book. That’s how my brother Yoshiharu started drawing comics: by copying Tezuka’s art. We didn’t have a desk, so he would use a wooden crate.

When did you start drawing?

When I was in second grade, inspired by my brother, I started drawing Tezuka’s characters in the street with a piece of chalk. Even at school, I used to draw on the blackboard. Then when I was about 12, my brother began to work professionally as a comic artist. I would come home from school and he would ask me to help with the easy parts, like inking some drawings. Those were the years when Yoshiharu Tatsumi was pushing the manga envelope with his gritty gekiga stories and a number of comic books such as Kage (Shadow) came out. I submitted one of my stories – it was about eight pages long – and surprisingly it was published! I was paid 1,000 yen – quite a lot for money in those days, especially for a youngster like me – and I was definitely hooked. I couldn’t believe I could get paid while having fun.

So you decided to apply yourself to manga drawing?

Well, not really. I’ve never really been good at drawing – even now, after all these years, I’m quite sloppy – but in those days, despite the initial success, I preferred horsing around with my friends to practising. I’ve always hated to work hard at something, practicing day in and day out in order to improve, and my manga were no exception. Then again, at the time I wanted to become a novelist more than a comic artist. With my friends, I even created a small mimeographed literary magazine (which didn’t last long), and my dream was to write a novel. I liked Kenzaburo Oe and Takeshi Kaiko who burst into the literary scene by winning the prestigious Akutagawa Prize one after the other – Kaiko in 1957 and Oe in 1958. I especially love Kaiko’s fiction and essays. There’s something special in people from Kansai [the area around Osaka and Kyoto]. They see things differently from people in Tokyo. He was a big influence on me. I used to imitate his style, and even now I like to reread his books. The downside of reading these people’s works is that you painfully realise you will never be able to write that well. I still write essays once in a while – for magazines or comic book reprints – but a novel is out of my range. And when I get stuck with my writing, I pull out a Kaiko essay collection for inspiration.

Your first comics were published in kashihon collections which mainly carried genre manga and were aimed at children. Did you ever feel their editorial policy put too many limitations on your art?

Not in those early days. Tezuka had laid the guidelines for drawing manga, and all the artists followed his blueprint. Comic stories were moral plays about good vs. evil, and you knew the good guys always prevailed over the bad guys. These rules were set in stone and taken for granted. In any case, there was no way a publisher would accept something different, that deviated from these rules. It wasn’t until Tatsumi’s gekiga came along that the bad began to win, so to speak.

Like Kurosawa Akira’s The Bad Sleep Well (1960), right?

Yes, something like that. I’m exaggerating a little, of course, but Tatsumi really changed the rules of the game. He showed that real life was more complicated than the world depicted in comics. Afterwards, the manga scene diversified, and increasingly original approaches became popular such as Sanpei Shirato’s period manga about social oppression and discrimination, and Shigeru Mizuki, whose approach was different from gekiga but still aimed at a more adult readership. Even my brother Yoshiharu was strongly influenced by Mizuki.

Your brother even worked on Mizuki’s GeGeGe no Kitaro, didn’t he?

Yes, they accomplished some brilliant work together, even though I must confess I like Mizuki’s was memoirs better. Even regarding GeGeGe no Kitaro, I prefer its earlier, darker period, when Kitaro was a more ambiguous, even mischievous character.

You earlier said you didn’t really care about improving your drawing skills. Have you ever thought about giving up your regular job and becoming a full-time professional manga artist?

Obviously, I would have been happy to work as a manga creator, but I never consciously pursued this career. Also, my family situation didn’t help in this respect: comic artists work in the solitude of their home, spending hours on their stories, but my house was the last place where I wanted to be. When I wasn’t working, I was out in the streets with my hooligan friends! Ironically enough, they often excluded me from their stunts because they cared about me. They used to say, you can become a comic artist, don’t waste your time hanging out with us. But I was hurt by their attitude. I would end up walking around the neighborhood alone, waiting for my two brothers to come home from work.

When did you leave home for good?

When I got married, at 24, I moved to my wife’s city, where we lived with their family and I joined their business, working in a hardware store and selling gas, which was much better than my previous life.

And what happened to your manga?

The year I got married was also the year my brother began his collaboration with Garo magazine. I seem to remember my brother told the editors I drew comics, too. On my part, I found in Garo a new kind of magazine where the author was truly free to draw whatever he wanted and the only limit was his imagination. I began to draw at night after work, little by little, and one of my stories found its way into the hands of Takano Shinzo, Garo’s managing editor, who sent me a letter inviting me to work for them. You can imagine how happy I was. In the beginning I contributed to nearly every issue, and I could see the money I earned was much better than my regular job, so when I was 27, I quit my job and devoted my whole time to manga. That was the most prolific creative stretch in my life. Unfortunately it didn’t last, and eventually I had to get back to my old job.

Your first contribution to Garo, “Up on the Hill, Vincent van Gogh…,” (1968) was originally conceived as a literary work. Why did you decide to turn it into a manga?

First of all, for practical reasons: I couldn’t wait to see my manga in the magazine, and working on “van Gogh” was the quickest way to accomplish that since I had already written the story. Also, I really liked the subject, and had done a lot of research on van Gogh. It was a story I very much cared about.

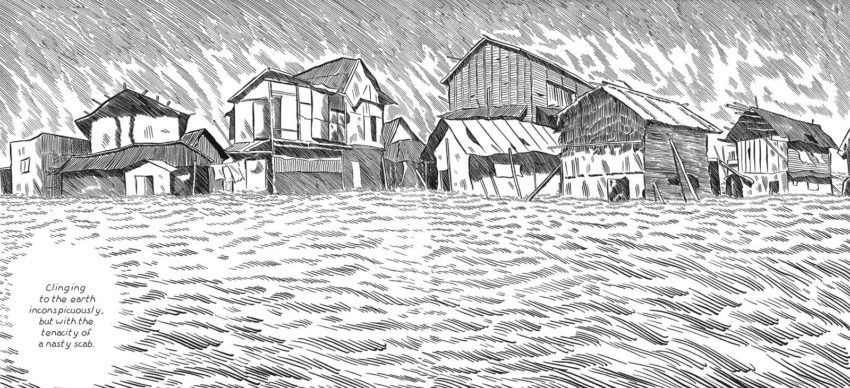

Yet your subsequent output was very different as you began to dig up your childhood and teenage memories. Most of your later comics either feature a middle-aged salaryman called Yokichi Aogishi or the kind of ruffians who populated your neighborhood in East Tokyo – particularly a character called Sabu Keisei. Why did you choose to portray their lives?

People like Aogishi and Sabu were everywhere. At my old job, for example, I had a chance to meet many of them, and I felt I understood their motives. At my old job, I was surrounded by adults. I was just fresh out of junior high school, but I could see through them. As a kid who had grown up being beaten at home on a daily basis, I had become good at reading people’s faces. Each one of them had a different story to tell, a different past, but they all shared the same war memories. Just by listening to them talk, I was able to imagine their life. My stories, in this respect, were just an accumulation of all these bits and pieces, filtered through my imagination. Telling those stories was a lot of fun. Sabu Keisei, for example, was a real person, but not as cool as I made him. I only caught a few glimpses of him, walking drunk around my neighborhood. More than seeing him, I heard people talk about him. So I had to make up the rest. Now, being a huge movie fan who liked characters like Shane in the western film of the same title, I loved the idea of the lone hero who rescued the girl before vanishing without a word, or fought to uphold his old-fashioned sense of honor.

This reminds me of actors like Ken Takakura and Bunta Sugawara who became yakuza movie stars in the 1960s.

Yes, they were hugely popular even among students of the New Left who theoretically didn’t share their characters’ conservative view of life.

By the way, in 1968-69 you were already 27-28 years old. I guess you weren’t really interested in the student movement and street demonstrations?

No, but I was once forced to take part in one. Sohyo (the General Council of Trade Unions of Japan) required that every factory and working place contribute a number of people to protest in front of the National Diet. They chose the “volunteers” by lottery. One day my name came out and there was nothing I could do to avoid it.

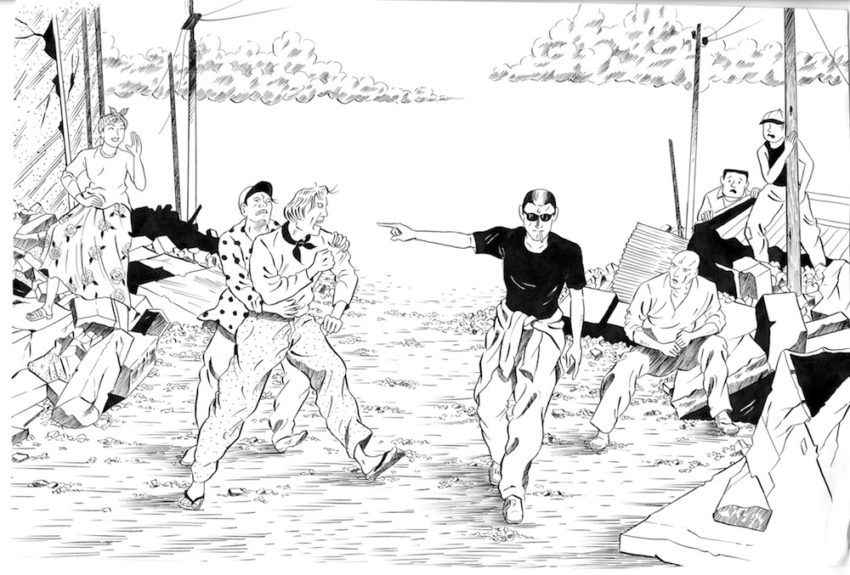

In the story called “Punk” (1971) the local thugs have a good laugh at the expense of a couple of hippy types.

You see, for people who came from a poor background and lived in slums, it was difficult to sympathize with young kids who spent their days raising a ruckus in the streets and then went home to their middle-class families. To my hooligan friends, they were just pampered privileged students who spouted half-digested slogans. It’s also true that for many regular working people, the place where I grew up looked like a different world. The titular punks in that story lived by their own rules, and their wild, uninhibited behavior looked quite scary.

Don’t you ever feel like drawing comics again?

I’m actually doing it right now! I started in 2018 and I have already produced a few installments so far, each one 28 pages long. Unfortunately, for the time being you can only read it online, but we plan to gather the first installments in book form. It’s called “Showa maboroshi” and is a sprawling tale starting soon after the war and featuring all my favorite characters from the past. I hope you’ll enjoy it.

Tadao Tsuge’s Trash Market (Drawn & Quarterly), Slum Wolf (New York Review of Comics) and Tale of the Beast (Black Hook Press) are all available now.